In the book “Preaching with Cultural Intelligence: Understanding the People Who Hear Our Sermons,”[1] Matthew D. Kim leads preachers to understand how to effectively communicate across many various boundaries including cultural and ethnic boundaries, gender and denominational boundaries, the boundaries of varying locations, and even the boundaries of various religions. Central to his work is showing how preaches may grow in cultural intelligence by understanding others and adapting to a variety of diverse listeners, so that the Gospel could be easily heard and received by those who are different than the preacher. Most hermeneutics may generally look at a bridging of the text’s meaning to its original audience to its application to modern society today. However, to Kim, “culture is life, and life is culture.”[2]

Culture, he argues, is a crucial part of biblical exegesis. Developing cultural intelligence (CQ) involves moving from a deep interest to understand the other into studying and gaining knowledge about the beliefs or values of the other. It then involves having a strategy or preparedness in how to rightly approach our interactions with the other before putting that plan into action where we intentionally engage and effectively practice our cultural intelligence. These four stages of developing cultural intelligence and becoming an embodied bridge to cultures, he calls, “CQ Drive,” “CQ Knowledge,” “CQ Strategy,” and “CQ Action.”[3]

As for the definition of culture, he shows it as a “group’s way of living, way of thinking, and way of behaving in the world, for which we need understanding and empathy to guide our listeners toward Christian maturity.”[4] In this, he reveals a model in which the way of thinking, an invisible reality, informs the visible realities of a culture’s way of behaving and living. In addition, he says, “all behaviors are culturally conditioned,” and so, in this way, the three components of culture may overlap or inform one another.[5]

He introduces an “homiletical template” that consists of three stages: 1. hermeneutics, 2. the hermeneutical bridge, and 3. homiletics.[6] Each stage has its own acronym to help preachers remember the components that make up each stage. Altogether it is a step by step process that helps structure a sermon that is deeply thoughtful, culturally engaging, and sensitive to the diverse audience.

For the hermeneutics stage, the acronym is “HABIT”, which stands for: 1. Historical, grammatical, and literary context, 2. Author’s Cultural Context, 3. Big Idea of the Text, 4. Interpret in Your Context, and 5. Theological Presuppositions. This process stands as Kim’s framework for interpreting Scripture. The “homiletical bridge” that this interpretation must cross over has its own acronym in the word “BRIDGE”, which stands for: 1. Beliefs, 2. Rituals, 3. Idols, 4. Dreams, 5. God, and 6. Experiences. A culture’s definition of greatness, of what is normal, of what is wrong or right, of worship and who God is, along with their experiences and values, may become the lens through which individuals of that culture view life. The preacher is wise to become familiar with these various components that make up a person or culture’s worldview. In this way, the interpretation of the meaning of a Scripture can be best communicated in preaching to these cultures’ true struggles and value systems.

The final stage of “homiletics,” is summed up in the acronym “DIALECT,” which stands for: 1. Delivery, 2. Illustrations, 3. Applications, 4. Language, 5. Embrace, 6. Content, and 7. Trust. In moving from a deep hermeneutical study that considered the original audience’s context and culture, the preacher crosses the bridge of understanding his current audience’s cultural background along with the meanings they may need from the text that apply to their own worldview. Yet this would not be complete without the final “homiletics” stage, where the preacher delivers his message in the dialect of those he preaches to. Using these various tools a preacher can help the listener feel understood, at home, and as though the message is being spoken to them in a personal and meaningful way. It involves truly caring for the listeners by intentionally thinking of them through the message. It involves speaking to them in words and illustrations that they understand and can relate to. It involves finding a common ground with them, relating to them personally, in the delivery of the message.

In this, a preachers’ ability to connect deeply with his or her congregants or audience depends on exploring these connections. Still, he says, “. . . interpreting Scripture with culture in view does not replace the historical-grammatical approach to hermeneutics.”[7] Instead, it involves understanding both the original audience’s culture and crossing the bridge into the various cultures in the preacher’s congregation in addition to the biblical exegesis. In this process of understanding the audience and navigating the intersection between hermeneutics and preaching to a culturally diverse group, the preacher must also look inward. He must honestly examine his own cultural background and biases, recognizing how this shape his views and interpretations of Scripture.

In the second part of his book, Kim shows how this homiletical template can be used to preach to a wide variety of culturally different audiences. In preaching to different denominations, Kim explains how preachers can focus on their already common ground in faith and mission. Unity among various denominations is to first and foremost be embodied by the preacher who is to have empathy, understanding, and respect to these denominational differences. He is to become a bridge of other churches in this relational approach. Moreover, in assessing what makes up the culture and experiences of a denomination the preacher can assess how her message will help build up that particular church.

In preaching to various ethnicities Kim shows how diversity in a congregation is important. It is all too often that the preacher, who is part of the majority culture, speaks to the majority culture only. This creates a spiritual environment where those of different backgrounds are strongarmed or pressured into becoming like the majority ethnicity and culture. Instead, understanding and engaging with various cultural backgrounds can inform a preacher’s message to speak to them, too, in a way that is personal. This is to do the opposite of what is usually done: minorities are ignored and not valued. Much of this can be attributed to a lack of care or motivation to understand the “other” among us, or even worse, fear or racism. Instead, the goal would be for the preacher to learn how to rightly celebrate the various ethnicities in his messaging in a language to speaks to their theological and cultural value systems, dreams, and various understandings.

A preacher is to have empathy and understanding in relation to the spectrum between the masculine and feminine spectrum that exists in both males and females, as well as the total uniqueness of each individual. This can be done by understanding the environmental factors, the factors of nature, and the factors of nurture that have formed the men and women of his audience. The preacher may, in this way, avoid any stereotypes or generalizations (or even work against those) that place wrong assumptions on the genders. Instead, practicing empathy and becoming familiar with the struggles and dreams of the men and women in her congregation, a preacher can give a balanced message that is inclusive to both genders and all individuals. Ultimately, a preacher’s message should be geared towards both men and women finding more depth in their identity in God and service to God.

Kim notes how various locations, such as urban, rural, and suburban settings, can each present their own challenges for preachers. These, however, are opportunities for the preacher to find areas in which to connect with the audience deeply. Each location has their own set of mindsets to explore and find a bridge to speak the Scriptures to. By identifying and pretending to preach to one particular individual in these various locations (with thier own theological presuppositions, dreams, and struggles), a preacher may begin to understand how his message will be perceived by the wider group.

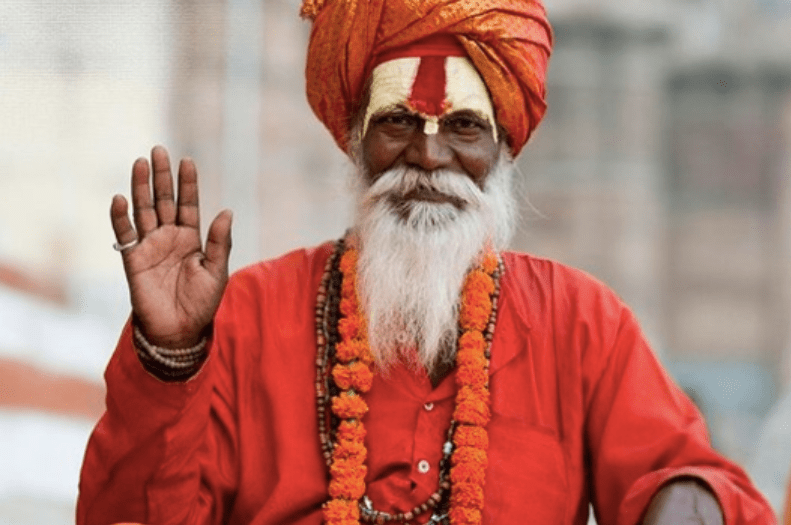

Finally, Kim discusses preaching amidst various religions in a way that opens up the Gospel to them, instead of shutting it down. Having an informed understanding of the various beliefs, practices and taboos of various religions, Christians can speak in an empathetic way that does not immediately shut a listener down by mocking or insulting them, for example. On the other hand, Christians, by understanding the various facets of beliefs, gods, dreams, and more of a different religion, can formulate a message that God truly wants to speak to them to set them free and bring them into his light and love. Preachers can ask themselves what it may be like to be a member of that different religion and what messages, illustrations, or deliveries would bring light and freedom to that group.

[1] Matthew D. Kim, “Preaching with Cultural Intelligence: Understanding the People Who Hear Our Sermons,” (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2017).

[2] Matthew D. Kim, 4.

[3] Matthew D. Kim, 6-8.

[4] Matthew D. Kim, 10.

[5] Matthew D. Kim, 11.

[6] Matthew D. Kim, 13-30.

[7] Matthew D. Kim, 15.